TWO COMMON GRAY SEAL PARASITES WITH DEVASTATING EFFECTS

Late spring/early summer is a common time of year to see young of the year gray seals pups haul out on many of Nantucket beaches to rest, sleep, warm up and recharge their batteries. Earlier in the year, most were born on one of Massachusetts’ desolate beaches, possibly during windy, cold or freezing temperatures.

Born with a fluffy white lanugo hair coat and minimal body reserves for warmth, they had to rely on the life-sustaining maternal bond established at birth between themselves and their mothers for survival. If they were fortunate enough to be born to a mother with good nursing skills, who was provisioned well enough to produce the required high fat content milk needed to rapidly build up a substantial blubber layer, then they were beyond one of the first major hurdles in their neonatal life.

During those early neonatal weeks, mom would stay by her pup’s side, overseeing its safety and nutrition until weaning, which occurred around 17-21 days of age. Hopefully during that time, our pup developed a thick blubber layer to maintain its body temperature during exposure to cold air and water as well as provide enough calories to sustain the pup’s metabolism as it went through the high energy and protein requirement of replacing the lanugo coat with a more permanent hair coat.

At this point, one would hope that the challenges of life would become easier for our young seal, but mother nature is unrelenting. The next hurdles were to learn how to enter the water, swim and forage for itself.

I begin today’s blog at this next hurdle in our young seals’ life, pictured above, who stranded along the south shore of Nantucket in May of 2021. The initial examination revealed an underweight seal of the year (approximately 5 months old), weak, with diarrhea, labored breathing and depressed mental attitude. The search for an off-island rehabilitation facility was made in hopes of providing some much needed care, but as is often the case, there were no openings available. Over the following 12 hours the seal was monitored, but with its rapidly deteriorating condition a decision was made to humanely euthanize.

Part of the function of the Marine Mammal Alliance Nantucket Stranding Team’s mandate through our permit with NOAA is to try to determine cause of death in those animals that strand and die on Nantucket. In most cases this requires a necropsy which is the term for an autopsy done on an animal.

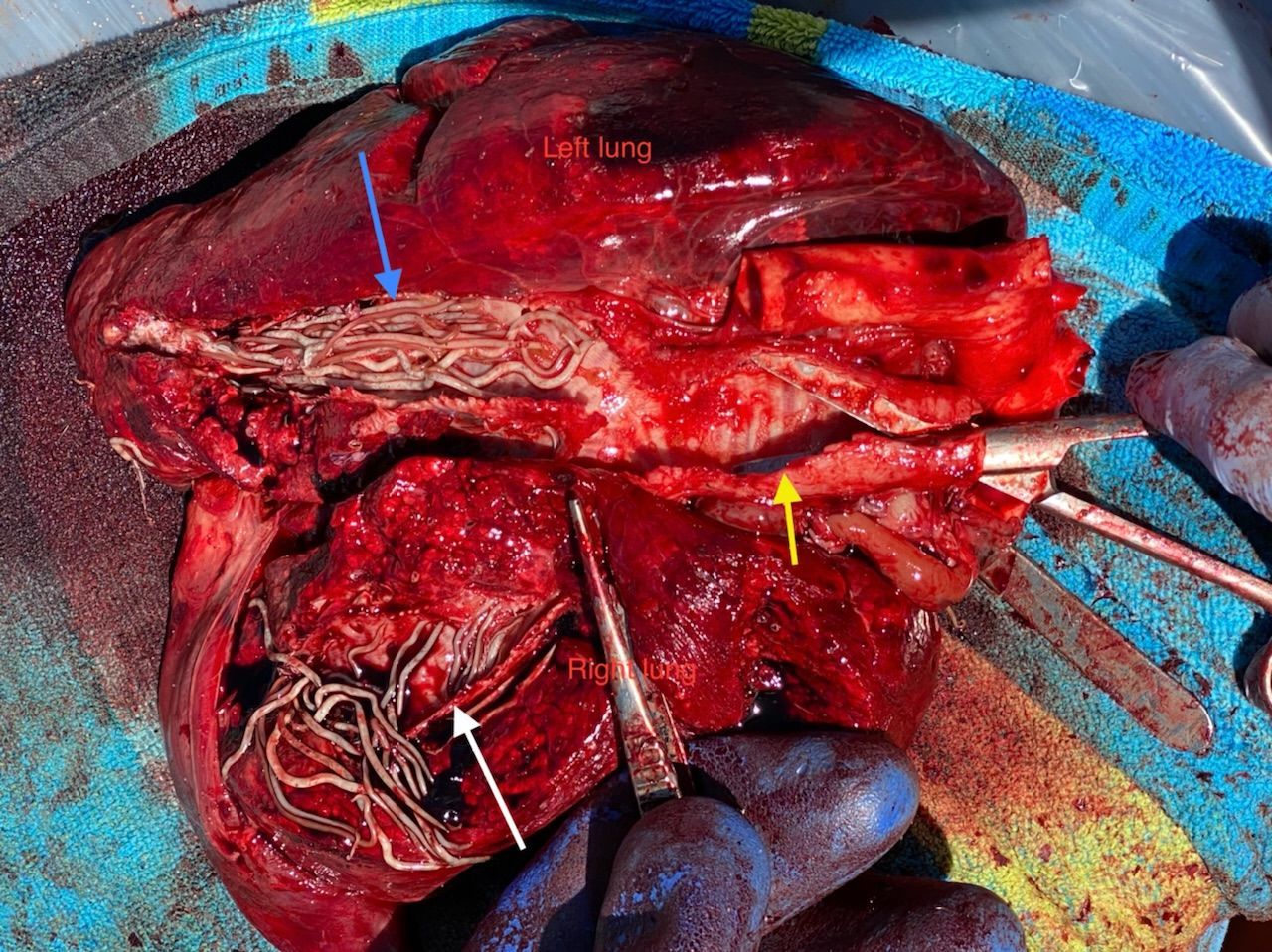

So what were the findings? Why did this pup who had overcome some major challenges in its early life finally fail to thrive? The answer is that two parasites, commonly seen in young seals, were causing significant pathology. The large lungworm of seals, Otostrongylus sp., were present aggravating a severe pneumonia. Also present were the acanthocephalan, Corynosoma sp., commonly called the thorny headed worm, which was causing intestinal perforations and peritonitis.

This picture shows multiple large lungworms residing in and obstructing the opened left mainstem bronchus (blue arrow) above and in the right mainstem bronchus (white arrow) below. The lungs are mottled and hemorrhagic from the parasites and a concurrent pneumonia. The scissors on the right are within the cut lumen of the trachea (windpipe) (yellow arrow). It is not hard to imagine the burden placed on this seal to perform normal respirations, let alone hold his breath for the dives needed to feed on his own.

This photo shows a segment of the intestinal tract with three white thorny headed worms moving through the intestinal wall and just to the right of them is an intestinal perforation (craterlike in appearance) contaminating the peritoneal cavity with infective material. A life- threatening infection of the entire abdominal cavity, called peritonitis, was well underway.

Both of these parasites were acquired when our seal pup transitioned from milk to eating fish. For the lungworm life cycle, adult worms in the airways of a seal produce larvae that pass up the airway to the back of the throat, where they are swallowed and then pass in the stools of the seal. These are then eaten by fish where the larvae become infective while encysting in the intestinal wall of the fish. When another seal eats the infected fish it picks up the lungworm.

A very similar life cycle is carried out for the Corynosoma sp. parasite, but in this case the adults produce eggs that pass in the stools and are ingested by an amphipod or isopod as a first intermediate host. Fish then ingest the first intermediate host to become the second intermediate host and the seal becomes infected when it eats the fish.

The more I learn about our marine environment and its creatures, the more I am amazed at the gauntlet of life that its inhabitants have to endure in order to survive. It is a perilous world out there for them, so we should all do our best to minimize the stress that they already have to endure. Remember when approaching seals on the beach, observe seals from a distance (>150feet), use binoculars and report any stranded, alive or dead marine mammals to the MMAN hot line.

Marine Mammal Alliance Nantucket’s Stranding Team’s Duties when a Dead Seal is Reported on the Beach